False Confessions Defense

False Confession Defense

Troy A. Smith brings over 24 years of highly competent and qualified litigation and appellate experience to the table as a former Criminal Defense Counsel for the United States Army and as a New York City homicide prosecutor.

Mr. Smith is widely regarded as a subject matter expert in litigating the coercive interrogation techniques used by law enforcement which may lead to a false confession. The insight he has gained into the criminal justice system will prove invaluable to you as an accused within that system.

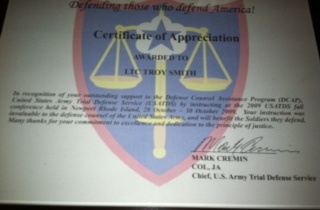

(Right: Attorney Smith presented with Certificate of Appreciation from Commander of US Army Trial Defense for teaching class on False Confessions.)

(Right: Attorney Smith presented with Certificate of Appreciation from Commander of US Army Trial Defense for teaching class on False Confessions.)

TEXT: United States Army Trial Defense Service –

Defending those who Defend America!

Certificate of Appreciation AWARDED TO LTC TROY SMITH

In recognition of your outstanding support to the Defense Counsel Assistance Program (DCAP), United States Army Trial Defense Service (USATDS) by instructing at the 2009 USATDS fall conference held in Newport Rhode Island, 28 October – 30 October, 2009. Your instruction was invaluable to the defense counsel of the United States Army, and will benefit the Soldiers they defend. Many thanks for your commitment to excellence and dedication to the principles of justice.

Mark Cremin

COL, JA –

Chief, U.S. Army Trial Defense Service

Attorney Troy Smith has also lectured on ‘Litigating the “False Confession” Defense to various organizations to include a Continuing Legal Education event sponsored by the Assigned Counsel Plan of the Appellate Division of the State of New York for the 1st and 2nd Departments, as well as the Bronx County Bar Association.

He has employed this defense successfully on many cases from Assault to Homicide.

If you have been charged with a felony where a cooercive technique was used to bring about a false confession, Attorney Troy Smith can help.

Contact Troy Smith now at (212) 537-4029, or use the contact form HERE.

HIGH PROFILE CASE DEFENSE BY ATTORNEY TROY SMITH

This case was profiled by John E. Reid & Associates as a reference and precedent setting case. It is used for discussing legal updates on criticisms of the use of false confession experts who attack the Reid Method of Interrogation that these psychological coercive interrogation techniques lead suspects to confess falsely. Find the complete case results below.

U.S. Army Court of Criminal Appeals.

UNITED STATES, Appellee

v.

Specialist Patrick C. McGINNIS, United States Army, Appellant.

ARMY 20071204.

19 Aug. 2010.

Headquarters, Fort Drum, David L. Conn, Military Judge, Colonel James F. Garrett, Staff Judge Advocate.

For Appellant: Lieutenant Colonel Troy A. Smith, JA (argued); Major Grace M. Gallagher, JA; Captain Jennifer A. Parker, JA; Lieutenant Colonel Troy A. Smith, JA (on brief).

For Appellee: Captain Sarah J. Rykowski, JA (argued); Colonel Norman F.J. Allen III, JA; Lieutenant Colonel Martha Foss, JA; Major Sara M. Root, JA; Captain Sarah J. Rykowski, JA (on brief).

Before TOZZI, HAM,FN1 and SIMS, Appellate Military Judges.

FN1. Judge HAM took final action in this case prior to her permanent change of duty station.

MEMORANDUM OPINION

TOZZI, Chief Judge:

*1 A panel consisting of officer and enlisted members sitting as a general court-martial convicted appellant, contrary to his pleas, of assault consummated by a battery on a child under the age of sixteen (two specifications), in violation of Article 128, Uniform Code of Military Justice, 10 U.S.C. § 928 [hereinafter UCMJ]. The panel sentenced appellant to a bad-conduct discharge, confinement for twelve months, and reduction to the grade of E1. The convening authority reduced appellant’s confinement to seven months, but otherwise approved the adjudged sentence.

Appellant claims as his sole assignment of error the military judge abused his discretion in denying the defense request for expert assistance “in the area of coercive law enforcement techniques which may lead to a false confession.” We agree and grant relief in our decretal paragraph.

BACKGROUND

Appellant was convicted of assault consummated by a battery for causing leg fractures to his eight-month old stepson, DW, and for grabbing his face. At the time of the offenses, appellant was a twenty-one year old high school graduate who had served on active duty for three years, and had a GT score of 90, described as “low average.” Appellant’s military occupational specialty was 31B, a military police officer. According to appellant’s platoon sergeant, Sergeant First Class (SFC) Sumalee Bustamante, appellant “lacks the intellect to be a noncommissioned officer … lacks common sense and is naive….” She further described him as “submissive and compliant” and “easily influenced by his peers, supervisors, and others in position[s] of authority. SPC McGinnis wants to please others and does not like others to be angry with him.”

The case first came to light when doctors at the Fort Drum medical clinic treated appellant’s three-year old stepdaughter for a broken arm and nine days later treated DW for leg fractures.FN2 United States Criminal Investigation Command (CID) Special Agent (SA) Christopher Vitatoe interrogated appellant for five and one-half hours regarding the allegations of abuse. During the interview, SA Vitatoe noticed appellant was “wiggling in his chair” and showing signs of discomfort. Appellant told the agent he was in some pain because he had a back injury for which he took prescription medication. Appellant admitted he was in discomfort but agreed to continue with the interview. Later, appellant asked for some pain medication because he did not have his prescription medication with him and SA Vitatoe offered him Tylenol, which he initially declined, but later accepted.

FN2. The members acquitted appellant of the offenses involving his three-year old stepdaughter.

For more than three hours of the interview, appellant denied any wrongdoing. Eventually, appellant admitted he might have caused DW’s injuries when he changed his diaper the night before. He admitted in his statement that he woke to DW crying and changed his diaper. When DW continued to cry, appellant admitted he became “frustrated,” “yanked” on DW’s legs, and “put [his] hand over [DW’s] mouth and squeezed his cheeks” to make him stop crying.

*2 Appellant initially said that he “lifted” DW’s leg while changing his diaper, but after he demonstrated the action to SA Vitatoe, he agreed with the agent’s description of the action being consistent with a “yank.” When appellant drafted a typewritten statement describing the incident with DW, SA Vitatoe reviewed the statement and suggested to appellant that he add “yanked” to his description of how he touched DW’s leg during the diaper change. SA Vitatoe then typed out a series of questions and typed appellant’s responses.

After the interview was over at approximately 0100, SFC Bustamante escorted appellant from the CID office. Appellant told SFC Bustamante that “he told CID that he did not hurt his kids and that CID would not take no for an answer.” Appellant also stated he “was exhausted and in a great deal of back pain” and he “just wanted the interview to stop so he could go home and see his wife and kids so he just told CID what they wanted to hear.” Sergeant First Class Bustamante notified appellant’s chain of command what appellant told her.

Defense Request for Expert Assistance

Six weeks before trial, defense counsel filed a written request to the convening authority, requesting he “appoint Dr. Richard Ofshe as a member of the defense team in the [f]ield of False Confession Analysis.” The convening authority denied the request and defense counsel filed a motion to compel with the military judge. In the motion to compel expert assistance, the defense also disclosed its intention to “offer the testimony of Dr. Richard J. Ofshe on the subjects of: (i) the influence effects of certain police interrogation techniques on the subjects of such interrogation; and (ii) the ability of police interrogation, in certain circumstances, to cause such subjects to make false inculpatory admissions.” Defense counsel further specified Dr. Ofshe’s anticipated testimony.

Dr. Ofshe will not state an ultimate opinion in the courtroom as to whether a false confession has actually occurred in any particular case. He would rather indicate to the jury the possibility of such a confession given the factors which have been systematically correlated to the existence of a false confession…. Further, the defense will not offer at trial any opinion by Dr. Ofshe as to the credibility of the accused.

Article 39(a) Session Regarding Motion to Compel Expert Assistance

At the motions hearing, the defense presented a reference section of a textbook,FN3 information on CID interrogation techniques, and a letter from SFC Bustamante. The defense otherwise relied on proffers of Dr. Ofshe’s testimony, cross-examination of the investigators, and argument to support his motion to compel expert assistance. After making extensive findings of fact, the military judge denied the motion.

FN3. The reference section of the textbook, “The Psychology of Interrogations and Confessions,” by Gisli H. Gudjonsson listing “900 to 1,000 articles that have been written on the subject of coercive police interrogation techniques and how they could potentially lead to the phenomenon of false confessions.” According to defense counsel, “a number of the articles are written by Dr. Richard Ofshe.”

The military judge’s findings included the following:

[D]efense counsel established [through cross-examination of the investigators] that agents are trained in psychological techniques to induce a person subject to interrogation to make admissions. They include: rapport building; minimization and moral rationalization; development of “themes” of culpability; so-called “good cop, bad cop” techniques (one agent confronts with incriminating facts and another separately offers sympathy or mitigation); persistent rejection of denials; evaluation of non-verbal clues[;] and control of the environment in which the interrogation takes place, among others.

< p>*3 In his conclusions of law regarding whether defense established the “necessity” requirement for expert assistance, the military judge found

Defense counsel … does not need an expert to present evidence that the phenomenon of a false confession has been defined and exists…. [T]he phenomenon has been long recognized as a matter of law. Agents Vitatoe and Maier both conceded the phenomenon in their testimony. It is likewise discussed in CID training materials…. What defense counsel seeks to obtain, however, is testimony by an expert suggesting there is a scientific method for determining whether, in a particular case, an admission or confession is false. Such evidence is impermissible and therefore there is no necessity for it.

In his conclusions of law regarding what an expert would accomplish for the defense, the military judge stated,

Defense ultimately would seek to permit[ ] a witness, under the mantle of “expertise” and with the special prerogatives of an expert witness under [Mil. R. Evid.] 702-703 to duplicate an evidentiary task well within the competence-and with regard to credibility, the sole prerogative of panel members…. [T]he “science” of “false” confessions has repeatedly been found to be, in the discretion of a trial judge, unreliable, and therefore inadmissible.

…

[F]alse confession theory is not the product of reliable principles and methods. No “expert” is able to apply such principles or methods reliably to the facts…. [T]hat persons [have] confessed … [and those] confessions were later scientifically discredited[ ] does not mean a psychologist or any other person can determine a method to evaluate the reliability of those confessions without knowledge of the existence [of] the objective scientific evidence demonstrating the confession is in fact false. In short, such testimony is Ipse dixit, not reliable evidence. It is simply another form of exculpatory polygraph evidence, with even less scientific methodology and objectivity…. Especially in the case of a trial before members, it is impossible to conceive how such evidence could be presented in such a manner that it would not be substantially more prejudicial than probative, since its only logical inference would be that such expert testimony is somehow predictive of the falsity of the accused’s admissions.

Finally, as a “prudential concern” in his conclusions of law, the military judge addressed his concern with “the defense timing of [the expert assistance] request.”

While the issue of challenge of the voluntariness of the accused’s statement was obvious from at least the Article 32[, UCMJ] investigation … the defense posed no request for expert assistance to the convening authority until 19 Sep [tember, four] months after referral and within a month of the then-established trial date.

…

While it did not weigh heavily in my consideration of the request for expert assistance in this case, given the highly suspect nature of the “expertise” at issue, it is a matter I wish to highlight to counsel, since late raising of these issues when the court has afforded counsel ample time to consider and raise such requests certainly militates against the likelihood of success of such motions, particularly when I am vested with discretion in such matters. Especially with experienced counsel, it smacks much more of gamesmanship than an inability to anticipate issues and make timely rulings for appropriate relief.

LAW AND DISCUSSION

*4 Rule for Courts-Martial [hereinafter R.C.M.] 703(d) authorizes employment of experts to assist the defense at government expense when their testimony would be “relevant and necessary,” if the government cannot or will not “provide an adequate substitute.” R .C.M. 703(d). See also United States v. Ford, 51 M.J. 445, 455 (C.A.A.F.1999). In addition, “upon a proper showing of necessity, an accused is entitled to” expert assistance. United States v. Burnette, 29 M.J. 473, 475 (C.M.A.1990), cert. denied, 498 U.S. 821 (1990). See also United States v. Bresnahan, 62 M.J. 137, 143 (C.A.A.F.2005) (“An accused is entitled to an expert’s assistance before trial to aid in the preparation of his defense upon a demonstration of necessity.”)

To demonstrate necessity, an accused must demonstrate something more than a mere possibility of assistance from a requested expert. An accused must show the trial court that there exists a reasonable probability both that an expert would be of assistance to the defense and that denial of expert assistance would result in a fundamentally unfair trial.

United States v. Gunkle, 55 M.J. 26, 31 (C.A.A.F.2001) (internal punctuation and citations omitted.) This court applies a three-part test to determine whether expert assistance is necessary. United States v. Gonzalez, 39 M.J. 459, 461 (C.M.A.1994), cert. denied, 513 U.S. 965 (1994). The defense must show: (1) why expert assistance is needed; (2) what the expert assistance would accomplish for the accused; and (3) why the defense counsel were unable to gather and present the evidence that the expert assistance would be able to develop. Id. A military judge’s ruling on a request for expert assistance will not be overturned absent an abuse of discretion. Gunkle, 55 M.J. at 32.

A military judge abuses his discretion when: (1) the findings of fact upon which he predicates his ruling are not supported by the evidence of record; (2) if incorrect legal principles were used; or (3) if his application of the correct legal principles to the facts is clearly unreasonable.

United States v. Ellis, 68 MJ. 341, 344 (C.A.A.F.2010) (citing United States v. Mackie, 66 M.J. 198, 199 (C.A.A.F.2008)). See also United States v. Lloyd, 69 MJ. 95, 99 (C.A.A.F.2010) (“The abuse of discretion standard is a strict one, calling for more than a mere difference of opinion. The challenged action must be arbitrary, fanciful, clearly unreasonable, or clearly erroneous.” (Internal citations and quotations omitted)).

The defense request and the military judge’s ruling both blur the distinction between a request for expert assistance and a request for an expert witness to provide testimony at trial. Defense counsel initially requested in his Motion to Compel Dr. Ofshe be appointed “as a member of the defense team as an [e]xpert in the field of coercive police interrogation techniques which may lead to a false confession[ ].” However, in the same motion, Defense sought “Dr. Ofshe to assist the defense in educating the members on the comprehensive research over the last [thirty-five] years that the use of coercive interrogation techniques employed by law enforcement may lead to a false confession.” (Emphasis added.) Further, in response to the military judge’s question of whether defense wanted Dr. Ofshe “to be qualified as an expert or … for assistance,” defense counsel responded he was “asking him to be qualified as an expert….” The military judge found it “impossible … to consider expert assistance without considering whether ultimately that assistance would yield admissible expert testimony under Daubert.”

*5 The Air Force Court of Criminal Appeals has urged practitioners “to distinguish between a request for an expert witness and a request for an expert consultant. An expert consultant is provided to the defense as a matter of [military and constitutional] due process, in order to prepare properly for trial and otherwise assist with the defense of a case.” United States v. Langston, 32 MJ. 894, 896 (A.F.C.M.R.1991).

The expert consultant is a member of the defense team and may receive confidential communications. Unless the consultant also testifies as a witness, the consultant is not subject to pretrial interviews by the other party, or to questions during the trial. By contrast, an expert witness may be called by either party or by the court. The expert witness testifies at trial and may be interviewed beforehand by both parties. Once the witness testifies, he or she is subject to cross-examination (and the normal rules apply.)

Id. (internal citations omitted).

In this case, the military judge considered whether Dr. Ofshe’s assistance would yield admissible expert testimony as part of his determination of whether expert assistance was necessary under Gonzalez. While we cannot point to other published cases where the military judge specifically has considered the likelihood of admissible testimony as part of the decision to grant or deny expert assistance, the two are guided by separate bodies of law. See Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579, 592-97 (1993) and United States v. Houser, 36 M.J. 392, 397-400 (C.M.A.1993) (establishing the factors that must be considered to determine the admissibility of expert testimony). But see Gonzalez, 39 M.J. at 461 (establishing the test for what defense must show in order to receive appointment of expert assistance). It logically follows the two requests should be considered separately by a military judge.

We note defense counsel did not object to the military judge’s consideration of expert assistance and expert testimony together and in fact, defense counsel himself, at times, commingled the two requests. Specifically, appellant noted a number of times in his motion to compel, his argument at the motions hearing, and his appellate brief to this court that part of the reason Dr. Ofshe’s expert assistance was necessary was because he would testify as an expert witness. We find the military judge prematurely considered whether Dr. Ofshe’s assistance would yield admissible testimony. He should have considered first whether the defense met the Gonzalez standard to show whether expert assistance was necessary and then separately considered whether any proffered expert testimony was admissible. However, our decision in this case does not rest entirely upon that determination. In addition, it is the further findings and conclusions set forth by the military judge that convince us that he abused his discretion in this case.FN4

FN4. We are also concerned with the military judge’s “prudential concerns” detailed in his conclusions and the role defense’s “late raising” played in his decision to deny the defense request. While the military judge may, within his discretion, deny a request for expert assistance when defense counsel has failed to make a showing of necessity, the military judge failed to explain how the late request demonstrated a failure to meet the Gonzalez showing of necessity. Though the military judge noted the late request did not “weigh heavily” in his consideration of the request for expert assistance, it did, apparently, bear some weight. Whatever weight the “late raising” played in his decision to deny expert assistance, without some link to a necessity showing, it was too much and an impermissible consideration under Gonzalez. This consideration by the military judge is yet another indicator that his decision to deny expert assistance was “arbitrary … and unreasonable.” See Lloyd, 69 M.J. at 99. Cf. United States v. Weisbeck, 50 M.J. 461, 465-66 (C.A.A.F.1999), rev’d on grounds, 58 M.J. 287 (C.A.A.F.2003) (abuse of discretion for military judge to deny continuance with “expeditious processing” as the only justification); United States v. Miller, 47 M.J. 352, 358 (C.A.A.F.1997) (listing the factors used to determine continuance grant).

Erroneous Finding

*6 Appellant first claims the military judge erred when he found “[d]efense offered no evidence that any admission of the accused is false.” Where a trial judge makes findings of fact, this court is bound by those findings unless they are clearly erroneous. United States v. Gore, 60 M.J. 178, 185 (C.A.A.F.2004). Defense counsel points to appellant’s statement to SFC Bustamante that “he told CID that he did not hurt his kids” and “he just told CID what they wanted to hear” because “he was exhausted and in a great deal of back pain” and “just wanted the interview to stop so he could go home and see his wife and kids” as some evidence appellant’s admission was false. We agree the military judge’s finding is clearly erroneous. Though appellant’s statements to SFC Bustamante were not an unequivocal denial of wrongdoing, it is some evidence his confession was false. Appellant’s statements were given close in time to his admission to CID. While appellant’s statements could be considered self-serving and while appellant never actually denied the acts he admitted to CID, namely “yanking” DW’s legs and grabbing DW’s mouth and squeezing his cheeks, the statements to SFC Bustamante were nonetheless some evidence that appellant’s admission was false. Thus, the military judge’s finding that appellant offered no evidence his admission was false was clearly erroneous and unsupported by the record.

In Bresnahan, the C.A.A.F. found the military judge did not abuse his discretion in denying the defense request for expert assistance, in part because “defense counsel never presented any evidence to suggest that [a]ppellant’s confession was actually false” and “has a ‘submissive personality so weak or disoriented as to make false incriminatory statements in response to accusations of serious criminal conduct.’ “ Bresnahan, 62 M.J. at 143. The court found those missing factors supported the military judge’s finding that defense counsel failed to demonstrate necessity for the expert assistance. Id.

In contrast, here, the military judge did find some evidence appellant had a submissive personality and erroneously found no evidence appellant’s confession was false. Thus, both factors missing from Bresnahan are present in this case. As a result, the military judge’s erroneous finding is particularly bothersome because, where the C.A.A.F. stated Breshanan was a “close call” despite the two missing factors, their presence in appellant’s case makes it all the more compelling.FN5

FN5. In fact, defense counsel argued this distinction to the military judge during the motions hearing and noted that the defense in this case presented evidence appellant’s confession was false. However, the military judge discounted the importance of evidence appellant’s confession was false, stating, “[T]he existence of independent evidence that an accused’s confession was false would seem to lower, rather than raise, the necessity of presenting evidence to attack the reliability of the confession through the use of an expert on ‘false’ confessions.”

Request for Expert Assistance

As our superior court has previously stated, “[i]n determining whether the military judge abused his discretion in denying the defense’s request for an expert consultant, each case turns on its own facts.” Bresnahan, 62 M.J. at 143. Reversal based on “an abuse of discretion involves far more than a difference in opinion.” Id. (citing United States v. Travers, 25 M.J. 61, 62-63 (C.M.A.1987)) (internal punctuation omitted). “The challenged action must be ‘arbitrary, fanciful, clearly unreasonable’ or ‘clearly erroneous.’ “ Lloyd, 69 M.J. at 99 (quoting United States v. McElhaney, 54 M.J. 120, 130 (C.A.A.F.2000)). “An abuse of discretion means that when judicial action is taken in a discretionary matter, such action cannot be set aside by a reviewing court unless it has a definite and firm conviction that the court below committed a clear error of judgment in the conclusion it reached upon a weighing of the relevant factors .” Gore, 60 M.J. at 187 (internal citations and quotations omitted). While the military judge articulated the proper law, he misapplied it, evincing that his decision was influenced by an erroneous view of the law. In addition, the military judge’s application of the relevant law as evidenced in the portion of his conclusions of law set out in the Background section, infra, was “arbitrary” and “clearly unreasonable.”

*7 While he does not use the term “human lie detector” in his written findings, the military judge’s conclusions clearly indicate his denial of expert assistance was predicated upon his determination that Dr. Of she’s testimony would never be permissible, “especially in the case of a trial before members.” There is no other way to read the military judge’s conclusion that it is “impossible to conceive how such evidence” could be legally relevant and pass muster under Mil.R.Evid. 403. This conclusion by the military judge reflects an erroneous view of the law.

We reiterate that the military judge should not have considered whether an expert would yield admissible testimony in determining necessity for expert assistance under Gonzalez. But it is his legal conclusion that coercive interrogation technique testimony could never be admissible as a reason for denying expert assistance that further supports our conclusion his decision was “arbitrary,” “clearly unreasonable,” and plainly runs afoul of our case law.

An opinion as to whether a person was truthful in making a particular statement regarding a fact at issue in the case is impermissible testimony. United States v. Brooks, 64 M.J. 325, 328 (C.A.A.F.2007) (citing United States v. Kasper, 58 M.J. 314, 315 (C.A.A.F.2003)). However, expert testimony may be appropriate to describe psychiatric conditions that tend to make a declarant in general more impressionable or susceptible to suggestibility by an interrogator. This is precisely what appellant sought to have Dr. Ofshe do-educate the panel on “how [CID’s] interrogation techniques are designed to break down the will of a suspect” and how a person like appellant who is “lacking in intelligence,” “submissive and compliant,” and “looks to please others” is particularly susceptible to coercive interrogation techniques.

In addition, defense counsel fully understood the limits of Dr. Ofshe’s testimony and explained those limits to the military judge repeatedly throughout the Article 39(a), UCMJ session.

[W]e’re not using [Dr. Ofshe] as [a] human lie detector test….[H]e will not state an ultimate opinion in this case, the ultimate opinion of whether this confession was a false confession.

…

Dr. Ofshe is not going to say that [appellant’s] confession is a false confession. He is merely going to … educate the jury that there has been [thirty-five] years of research on this subject dealing with thousands of articles and numerous amounts of … experts watching interrogations … he’s going to educate [the panel members] on the measures that the CID agents and the interrogation techniques that they use.

…

Dr. Ofshe is not going to opine that [appellant’s statement was involuntary or that it was a product of coercion and manipulation] because I don’t want him to opine that and he wouldn’t opine that because I’d be using him as a human lie detector test.

…

*8 [Dr. Ofshe] is not going to testify [that this is a false confession] because that’s a matter for the jury to decide.

Nonetheless, defense counsel’s assurances fell upon deaf ears. The military judge concluded, without the benefit of actually hearing any expert testimony of the scientific basis supporting the methodology behind the study of coercive police interrogation techniques which may lead to false confessions, that such evidence was “simply another form of exculpatory polygraph evidence.”

Some courts have found this type of testimony to be inadmissible and no published case from our superior court has found a military judge abused his discretion in denying its admission. It is also true there has been a history of skepticism with regard to the theory underlying this testimony. See Major Peter Kageleiry, Jr., Psychological Police Interrogation Methods: Pseudoscience in the Interrogation Room Obscures Justice in the Courtroom, 193 Mil. L.Rev. 1, 18 (Fall 2007). However, recent literature, including recently completed research and analysis by social scientists, suggests the theory is reliable. Id. at 19.

Contrary to the military judge’s assertion, however, other trial courts have found this type of testimony admissible.FN6 See United States v. Olafson, 2006 WL 1663011 (N.M. Ct.Crim.App. 8 June 2006) (unpub.) (Doctor Jerry Brittan permitted to testify that appellant fit the criteria for those who give false confessions). See also United States v. Shay, 57 F.3d 126 (1st Cir.1995) (finding trial court erred in excluding expert testimony regarding defendant’s mental condition that caused him to give false confession); United States v. Raposo, 1998 WL 879723 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 16, 1998) (admitting expert testimony on false confessions); United States v. Hall, 974 F.Supp. 1198 (C.D.Ill.1997) (permitting specified expert testimony on the subject of false confessions); State v. Buechler, 572 N.W.2d 65, 72-74 (Neb.1998) (holding that the trial court committed prejudicial error when it excluded expert testimony on false confessions); Callis v. State, 684 N.E.2d 233, 239 (Ind.App.1997) (affirming trial court’s decision to admit, on limited grounds, expert witness testimony regarding police interrogation tactics); State v. Baldwin, 482 S .E.2d 1, 5 (N.C.App.1997) (holding that the trial court erred in excluding expert witness testimony that police interrogation tactics made defendant susceptible to giving a false confession). See also United States v. Griffin, 50 M.J. 278, 285 (C.A.A.F.1999) (Sullivan, J., concurring in the result) (disagreeing with “the majority’s conclusion that no error occurred in the exclusion” of expert testimony on coerced confessions). In addition, neither this court, nor our superior court has found this type of testimony to be per se inadmissible. See Griffin, 50 M.J. at 284-85.

FN6. According to the record, one of the “premier experts” in the field of false confessions, Dr. Saul Kassin, testified at a Fort Drum court-martial as an expert in the field of false confession analysis in United States v. Bickel, ARMY 19990506 and Dr. Ofshe “has been qualified as an expert in the field of coercive police interrogation techniques which may lead to a false confession in three [courts-martial]….”

The military judge’s language, articulating the notion that such testimony would never be admissible in a trial before members and therefore that expert assistance in this area is not necessary, renders superfluous case law laying out the legal framework under which such expert testimony should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis for admissibility. Daubert, 509 U.S. at 592-933; Houser, 36 M.J. at 397. Testimony concerning coercive interrogation techniques and those personality traits that make one particularly susceptible to those techniques could assist the members in understanding the similarly counterintuitive behavior of admitting to criminal acts that one did not commit. Analogous to coercive interrogation technique expert testimony is expert testimony regarding “rape trauma syndrome.” Houser dealt with the use of rape trauma syndrome testimony to explain the counterintuitive behavior of rape victims. 36 M.J. at 399. See also United States v. Suarez, 35 M.J. 374, 376 (C.M.A.1992) (permitting experts to testify about counterintuitive behavior of child victim of sexual assault, including why a child may render inconsistent statements, recant allegations, fail to report or delay reporting abuse).

*9 As the military judge conceded, “false confessions” do occur. Expert testimony could assist the members in understanding why they occur without running afoul of any longstanding prohibition against “human lie detector” testimony, that is, without stating that the confession at issue is false. The judge predicated his ruling on his view that it was “impossible to conceive” this type of testimony was admissible. He was wrong. See United States v. Hall, 93 F.3d 1337, 1345 (7th Cir.1996) (“[E]ven though the jury may have had beliefs about [false confessions], the question is whether those beliefs were correct. Properly conducted social science research often shows that commonly held beliefs are in error. Dr. Of she’s testimony, assuming its scientific validity, would have let the jury know that a phenomenon known as false confessions exists, how to recognize it, and how to decide whether it fits the facts of the case being tried.”); United States v. Belyea, 159 F. App’x. 525, 530 (4th Cir.2005) (unpub.) (The trial court’s suggestion that “expert testimony on false confessions is never admissible …. is erroneous as a matter of law because it overlooks Daubert’s general requirement for a particularized determination in each case.”)

Such an interpretation demonstrates an erroneous view of the law. This is true regardless of any other court’s determination regarding the admissibility of coercive interrogations and false confessions testimony. Instead, the military judge’s arbitrary decision demonstrated his resistance to applying the law to the relevant facts to determine whether, in a particular case, the proffered testimony was admissible. He then bootstrapped this rationale to deny the defense request for expert assistance.

Here, appellant “made a specific request for expert assistance necessary for his defense on a central issue in a closely contested case. The military judge erred in denying the defense the equal opportunity to obtain evidence and witnesses guaranteed by Article 46 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice.” Lloyd, 69 M.J. at 101 (Effron, J., dissenting). While defense counsel was able to consult briefly with Dr. Ofshe, educate himself on coercive interrogation techniques and obtain CID’s training slides, he was hindered from fully preparing his defense by having an expert as a member of his defense team. While defense counsel presented evidence of the coercive techniques investigators use during suspect interrogations, he was forced to do so via cross-examination of government witnesses without expert assistance. See United States v. Lee, 64 M.J. 213, 217-218 (C.A.A.F.2006) (finding abuse of discretion where military judge found that “since the defense counsel had the opportunity to discuss [evidence] with the [g]overnment’s expert, there was no need for a separate defense expert”); United States v. Warner, 62 MJ. 114 (C.A.A.F.2005). While he was able to present the concession from the same CID agents who took appellant’s confession that false confessions do occur, defense counsel was prevented from obtaining expert assistance, which might have allowed him, through cross-examination or direct testimony, to present evidence to the panel on the study of coercive interrogation techniques, why they work, and how some of appellant’s specific characteristics and the circumstances of this case may have made appellant particularly vulnerable to the interrogators’ coercive techniques. Defense counsel was also unable to obtain from the CID agents a concession that any of their interrogation techniques could have led to unreliable admissions in this case. Instead, as a result of the military judge’s error, “the defense was compelled to rely on arguments by counsel drawing inferences from lay testimony without the benefit of” expert assistance to prepare for trial and potentially, expert testimony to educate the panel regarding the study of coercive interrogations and the study of false confessions. Lloyd, 69 M.J. at 102 (Effron, J., dissenting).

*10 The denial of expert assistance to appellant in this case, deprived appellant of “ ‘relevant and material, and vital’ “ assistance and possible testimony. United States v. McAllister, 64 M.J. 248, 252 (C.A.A.F.2007) (McAllister II ) (citing Washington v. Texas, 388 U.S. 14, 16 (1967)) (internal punctuation omitted). The effect of the military judge’s ruling “den [ied] him the right to present a defense,” a “fundamental element of due process of law.” Id. Where there is an “error of constitutional magnitude [it] must be tested for prejudice under the standard of harmless beyond a reasonable doubt.” United States v. Kreutzer, 61 MJ. 293, 298 (C.A.A.F.2005), (citing Chapman v. California, 386 U.S. 18, 24 (1967)); United States v. Sidwell, 51 M.J. 262, 265 (C.A.A.F.1999). A constitutional error is harmless beyond a reasonable doubt when “beyond a reasonable doubt, the error did not contribute to the defendant’s conviction or sentence.” Id. (citations and internal quotations omitted). Said differently, this court must be convinced “there was ‘no reasonable possibility’ “ that the lack of expert assistance and possible testimony from an expert witness regarding false confessions and coercive interrogation techniques “ ‘contributed to the contested findings of guilty.’ “ McAllister II, 64 M. at 253 (citing Kreutzer, 61 M.J. at 300).

Appellant requested the expert assistance on the sole and central issue, the “linchpin” of the case-the validity of his statement to CID. See United States v. McAllister, 55 MJ. 270, 276 (C.A.A.F.2001) (McAllister I ). In closing arguments, the government twice called appellant’s statement “the smoking gun” in their case whereas appellant’s sole defense was that his statement was false. The Supreme Court has observed an accused’s confession is strong evidence and the accused should be given ample opportunity to confront it:

Confessions, even those that have been found to be voluntary, are not conclusive of guilt….[S]tripped of the power to describe to the jury the circumstances that prompted his confession, the defendant is effectively disabled from answering the one question every rational juror needs answered: If the defendant is innocent, why did he previously admit his guilt?

Crane v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 683, 689 (1986). This was a closely contested case, with conflicting testimony on whether the events, as appellant described them in his statement, actually caused DW’s injuries. There is no question appellant’s statement played a significant role in the panel’s decision to hold appellant responsible for DW’s injuries. This is particularly true where the defense expert witness, qualified in the areas of pediatric orthopedic surgery, mechanism of injury, and blunt force trauma, inter alia, testified that with regard to DW’s injuries, he did not believe “any single pulling up of the leg to change a diaper would form fractures of this magnitude.” He further testified DW’s injuries were more “likely” from DW falling from a height. In this “close case, the defense was denied the opportunity to explore the potential for expert testimony on the critical issue of guilt or innocence.” Lloyd, 69 M.J. at 103 (Effron, J. dissenting) (citing Gunkle, 55 M.J. at 32). We simply cannot conclude the military judge’s “arbitrary” and “clearly unreasonable” decision that prevented the defense from critical preparation and presenting critical evidence was harmless beyond a reasonable doubt.

*11 As a result of the military judge’s error, appellant was also denied the “opportunity to obtain witnesses and other evidence” to “develop evidence” and “test and challenge the [g]overnment’s case” as required by Article 46, UCMJ. United States v. Warner, 62 M.J. at 118. See also, UCMJ art. 46. For the same reasons stated above, the Article 46, UCMJ violation was not harmless. See UCMJ art. 59(a). We “cannot say, with fair assurance, after pondering all that happened without stripping the erroneous action from the whole, that the judgment was not substantially swayed by the error….” Kotteakos v. United States, 328 U.S. 750, 765 (1946.

CONCLUSION

Upon consideration of the entire record, including those matters personally specified by appellant, the findings and sentence are set aside. A rehearing may be ordered by the same or a different convening authority.

Judge HAM and Judge SIMS concur.

Army Ct.Crim.App.,2010.

U.S. v. McGinnis

Not Reported in M.J., 2010 WL 3931494 (Army Ct.Crim.App.)

END OF DOCUMENT